The Human, A Wondrously Broken Machine

Adam Tufts

Mela Johnson

Hours melted away beneath the scorching California sunshine before I found a moment of pause to gaze down at my sweat-slicked body: sawdust coats my limbs, the blister on my thumb glows a festering red, and my head pounds with what seems to be an onsetting illness. Yet as I registered the soreness surging through my thighs and forearms, I couldn’t help but allow flickers of a smile creep across my face. I had spent the past week feverishly chopping wooden beams and then assembling them together again in hopes that they would resemble something akin to a desk. My endeavor was punctuated by plenty of pitfalls, between extreme temperatures warping the planks to a power drill deciding that clockwise revolutions were a thing of the past. By its end, the construction process had left my garage a mess of wooden scraps and my body exhausted – but there they stood, nine wooden desks, in their polished glory. Some desks teetered on uneven legs, others lacquered with an uneven coat of polyurethane, but they were complete, the fruit of my lacking expertise, imperfect technique, and physical pain. And there was something so perfect about that.

This haunted me. These ponderings of perfection followed me out the garage and to my less haphazard bedroom desk, where, before I knew it, I was browsing the paragon of human creation that is the Internet. My YouTube recommendations rapidly shifted from “How To” carpentry videos to philosophy lectures and debates. Hurriedly, I typed: “What is perfect? What is the perfect human? How do I feel perfect?” A tidal wave of information inundated my sixteen-year-old brain, but one concept seized my attention, as it does the attention of virtually anyone who inputs the word “philosophy” into Google: Robert Nozick and his Experience Machine.

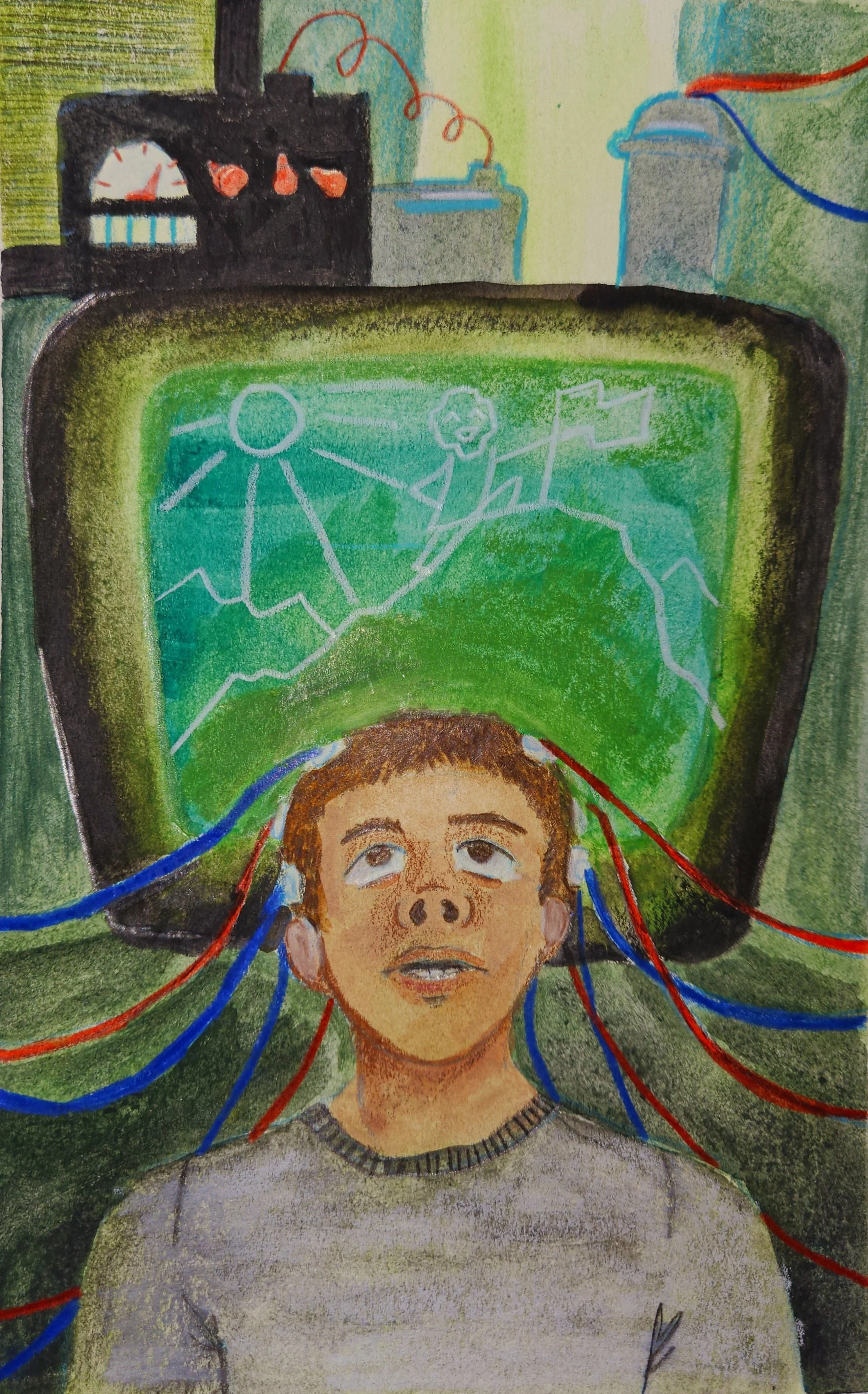

The Experience Machine is a thought experiment meant to probe hedonism (a philosophical paradigm that elevates pleasure as the ultimate good), wherein an individual is granted the opportunity to have their brain stimulated such that they feel perfect. If the principal project of one’s life were to summit Everest, they would feel the Himalayan mountain breeze tousling their hair. If they wished to become the next revered American novelist, they would experience the sensation of penning each word to paper before finally achieving nationwide success. The catch is that none of this would actually occur; the individual would remain in some nondescript laboratory, connected to an unspecial machine that transfers their consciousness to a different utopic realm. Think Avatar.

This machine posits a perfection – all the pleasure one could ever fathom transmitted directly to one’s brain. No flaws, no nuance, just absolute, encompassing pleasure. Yet Nozick rejects the Machine and the hedonistic ideals it embodies. He argues that there is more to life than an elementary pleasure-pain binary, that there is something to be gained in refusing this “perfection.” He argues the essence of life is that it’s yours, that it’s imperfect.

This launched my thoughts into a spin. Why were my splintered desks perfect? Why did I feel so strongly about their perfection? What was it that made them perfect? Everyone should desire perfection, but I loved my wobbly desks; I loved the calluses on my palms; I loved the sawdust that still lingers in the nooks of my garage. The Experience Machine eliminates this toil, it centers absolute, perfect pleasure – but I found its perfection undesirable. How can this be? This paradox stalled my thinking; I became unable to reconcile these divergent conceptions of perfection. I remained haunted. Analysis paralysis.

But these thoughts eventually slipped into the oblivion of memory, and suddenly I was 18, selecting classes for my first semester at Yale. At least five minutes of each class was devoted to broaching the topic of ChatGPT and AI language models, of which I was completely ignorant. Humanities professors pleaded with their students to reject the assistance of AI, labeling it a “dishonest shortcut” that undermines academic integrity. So I paid no heed to ChatGPT or its analogs. For about two months. It was then that the haunting considerations of perfection sank their claws into my mind once more.

I recall tentatively probing the language model about my essay topic at the time – something about Melville I’m sure – and watching, awestruck, as I received a cogent response (multiple, at that!) in a matter of seconds. In the blink of an eye all the words I could have wanted to string together into some compelling argument blinked before me, and I was filled with horror. My first thought was not how I might be able to integrate this computer generated response into my writing, rather it was occupied with the perfection that seemed to manifest itself in mere moments – a perfection crafted with automatic, clinical precision. And there was something so dissatisfying about that, so imperfect.

These language rendering models have a unique creative capacity insofar as they gather source material from the largest known pool of human creation (the Internet!) and can couple this boundless creativity with their machinelike (near-perfect?) efficiency. It wasn’t long before I drew a parallel between AI’s creative process and the Experience Machine – both serving as mechanisms by which one is capable of arriving at an “optimal” status without the labor and pain required to arrive at such a point. I perceived each as a means to bypass the process (the “journey”), to reap the fruits of labor with no labor, to forsake all creativity for creation. Further, I noticed that I was not alone in this sentiment. Beyond my teachers’ worries about how AI might stain academia, society at large seemed to express at least some degree of dread towards its popularization. Whether it was creatives resisting the integration of AI into their fields on the basis that it steals their work or attorneys fearing job replacement by a machine able to accomplish the same tasks with enhanced efficiency, the general apprehension surrounding AI’s usage was palpable. To me, it seemed as though the Experience Machine was loosening itself from the title of a mere thought experiment and beginning to worm its way into reality. It was as though the progression of efficiency was reaching a sort of asymptote, labor time slashed with AI-facilitated human ideation, research, and craft. Was I meant to believe that these AI language models, quasi-Experience Machines in their own right, were more perfect than the human minds which created them? Because I didn’t. And it seemed like society at large, with whole economies running on the premise that toil bears value, agreed with me.

Similar to how my confusion persisted surrounding why I felt perfectly about my desks, I was also uncertain about the converse: what specifically was it about technology that made it seem so imperfect, especially with regard to artificial intelligence? Fittingly, given that Yale academics ignited my curiosity surrounding artificial intelligence and its relation to perfection, it was also a Yale class that offered me answers.

One of my courses within the History of Science department mentioned the 1960s experimental language processing program, ELIZA, created by Richard Weizenbaum (link to study). Employing a pattern-matching and substitution methodology, Weizenbaum set out to develop a means of simulating conversation between humans and computers. Interestingly, Weizenbaum’s intent was to reject the claim that machines could ever exhibit behavior indistinguishable from humans via a kind of Turing test (a method of interrogating the similarities and discrepancies between computer vs. human-generated language). This revolutionary language model was programmed to serve as a sort of pseudo-therapist to its users, specifically trained in Rogerian, or person-centered, therapeutic techniques. The central philosophy of Rogerian therapy elevates the client as the expert of their own life – the therapist simply acting as a conduit through which individuals discover their own solutions. Thus, much of ELIZA’s dialogue manifests as calls for the user to reflect: Why do you think you feel that way? Why do you think that elicited such a response? How did your emotions affect you? And, much to Weizenbaum’s surprise, this approach was successful. Many users reported feeling better, emotionally, after conversing with the program, with Weizenbaum’s own secretary requesting privacy so that she could focus on her intimate exchange with the chatbot. Indeed, Weizenbaum even noted that a portion of users seemed to attribute human-like feelings to ELIZA, such as desires for confidentiality and interpersonal connection. Certain early users of the chatbot were convinced of ELIZA’s intelligence and true understanding of their personal dilemmas, despite Weizenbaum’s insistence on the contrary.

Following this lecture, I initiated my own discussion with an ELIZA replica and was shocked by the ELIZA I encountered. Accustomed to the refined, thorough, and listed answers that ChatGPT usually provided, ELIZA’s short and basic interrogative phrases first struck me as almost primitive, lacking in some capacity. Recollections of Weizenbaum’s secretary flitted through my mind during my dialogue with ELIZA: there was something about this often confused chatbot that appealed to her emotional sensibilities. This sentiment starkly contrasted the general apprehension surrounding ChatGPT and the enormous pool of information it wields in all dialogues – it rarely becomes confused, rarely is unaware, rarely is at a loss for words. Yet in the plethora of advice and information ChatGPT offers, I saw no humanity; I saw a robot endeavoring to complete my request. With ELIZA, I felt more compelled to unveil my secrets and welcome intimate exchanges. From its errors and imperfection, I developed trust and even a kind of connection. It understood and questioned me in a manner that ChatGPT could not replicate. I discovered something great emerging from ELIZA’s imperfection.

Whether or not this greatness related to ELIZA’s proximity to the imperfect nature of humanity was not immediately clear. Accepting this premise would indicate that the human condition exists on a plane that is wholly imperfect and marked by incomplete understanding. It would suggest that humans have a proclivity to dwell in the uncertain, to unsnarl and then reconnect the threads of the unknown into a tapestry of one’s own creation. And yet this is the conclusion my thoughts repeatedly led me to: that humanity, despite incessantly “expanding the bounds of knowledge,” relies on the unknown. Humans crave an existence of dynamism, progression, and process. After all, without progression there is no learning, only unsullied knowledge; there is no solving, only solution; there is no action, only completion. So while people often lament the occasional incompetency of ELIZA, of themselves, of their friends, seldom do they recognize how their humanity is inextricably entwined about these insufficiencies. Humans shackle themselves to the fetters of imperfection because it is only there that they can watch the shadows of obscurity dance, that they can witness the delicious potential of the unknown, that they can truly feel alive. The fetters of imperfections… Fetters? Fetters!

Suddenly, my thoughts shoot back to my bedroom desk, Nozick not the sole philosopher I encountered in my Internet search. In fact, I can clearly remember one other image, besides the Experience Machine, which left an indelible imprint on my memory: Plato’s Cave. A scene is cast in my imagination. I see humans, chained to the cavern floor, watching shadows traverse the wall before them, a product of moving puppets and a flame blazing behind them. I look closer. The humans’ mouth-corners are faintly twisted upwards into the slightest of smiles; their eyebrows are knit in concentration, hardly perceptible; their lips are whiskers-lengths apart. The prisoners’ expressions tell all. Their imprecise and incomplete perception of reality does not haunt them – indeed, they track the movement of shadows with eager fascination.

Meanwhile, the fire outside their gaze heats the backs of their heads and roars with intent to consume. I imagine this fire leaping at the wooden puppets and incinerating them into formless ash. Now, the humans are met with no dance of shadows, and they stare at a wall evenly lit by the flames raging behind them. I witness as the glaring light melts away every trace of contentment and intrigue which once animated their faces. There is no darkness. There is no shape. There is no movement. There is only light. Comprehensive, absolute and unbearable light.

And those fetters of imperfection… Or did I mean feathers? As in flight? As in liberation? Because perhaps this is precisely what the imperfect accomplishes. It keeps the ball of humanity rolling onwards. It provides us with wobbly desks and faulty psychotherapists and illusory shadows. It fans Plato’s flame further and further from us. Yet as society innovates, pushing the limits of efficiency to unimaginable heights, and as the potencies of technologies like artificial intelligence crescendo, we find the Perfect flicking its heat ever closer to our faces. And this is what haunts us. We paint accomplishment, completion, and creation in vibrant, exciting hues – we tell ourselves that all we desire is some terminal point, some goal. But it is this finality which horrifies us all the same. Because once we’ve written that one essay, gotten that one grade, secured that one job, bought that one thing, what do we do then? What are we to do amidst this primordial clash between the Perfect and the Human?