the color of void

Artifact #004, collected by S. Feng, re-drawn by E. Cai. Dated circa A.S. 293, found in Mt. Thymos, Planeta Lux. Excerpted from anthology Cult Accounts: Anthropological Studies of Religious Groups in Post-Reversal Worlds.

E. Cai

I wonder how much sunlight is inside of me. The other day I watched a butterfly lie on the ground. Its wings were like pieces of paper beginning to curl with age, but it had been born just weeks ago. I could tell by the color of its wings: they had just lightened to a pale, opalescent green, milky and marbled with spots of even lighter lime, framed with black, inky brackets. That was what a Pollock butterfly in its adolescent month looked like. But lately the flowers in the mountains around us were beginning to wilt, so butterflies that drank their nectar were dying off in droves. A couple of them landed at the empty fountain in front of our temple, maybe seeking water from its spout, but it had been dry for years. Their broken spines lay limp on the edge of the white clay forming the lip of the fountain, their wings fluttering weakly. This one crawled to the oblongs of shade cast by the fountain on the ground. I watched it die, releasing its last breath from its spiny black chest, its antennae glinting under the harsh sunlight. The intense heat had bleached the color of its wings, made the jade-green as light as fresh moss, as if rotted through with white paint. It was a terrible color to behold.

In the front yard of our temple, there is this fountain, and beneath it are sun-marigolds that spout and rise up, their orange vines tangled thickly around the base of the fountain and sprouting upwards, fat and brilliant. Their petals are plump: they photosynthesize eagerly. Some species adapted. Everything feels heated and heavy around me, like a sweet syrup. The rest of the front yard sprawls for at least a few hundred square feet, the barren dirt at the apex of this mountain sprouting yellow and white weeds that sway in the brief breeze that comes, that shivers through my skin with delight. The hairs on the back of my neck stand up. A bandana is wrapped around my forehead, and sweat trickles down my neck and drips onto the dirt. I close my eyes. I am crouched by the fountain. There are few other structures before entering the temple that provide shade: for we are meant to worship the sun, to idolize the heat.

Today is the Undoing. I can feel the sweat all over my body. I can see the body of the silt temple behind me like a quiet thing, ready for release.

I think things that burn are things that were so holy they needed to be sacrificed.

Behind me is the entrance to the temple, erected out of mud and silt from this mountain: rust-colored adobe, stone, loess, and earth packed upwards into a temple, each door-frame and frieze carved with fine-toothed combs and picks into murals that depict the Great Reversal. When my mentor Pila was four, she fell off the ceiling of one of the roofs while she was assigned to help sculpt a scene from her family’s life, as all children do when they turn seven; she slid off and fell, and broke her arm. This is what she tells me.

Nobody is awake yet. I creep forwards, ensuring that my steps are silent. It is possible that there are mentors meditating in the courtyard of the temple. It is possible that some are watching me from the high perches above, or the pavilion that lies at the back of the temple.

Before I open my eyes to examine the sight again, I know in painful and intimate detail the scene before me: it has been ingrained in me like a blueprint I am not allowed to forget. There are two layers of an electric fence that can immediately send hundreds of volts through a human body if turned on. During the hours in which travelers are allowed to make pilgrimages, the fence is turned off. There are four watchtowers that are tall, thin slits in the top floors of the temple, where the elder monks patrol sometimes. I do not know how often they are staffed, but last time it was a shout from a young girl there, still rosy-cheeked and baby-eyed, that eventually brought me to my knees. There are rows of catapults inside of the silt windows loaded with miniature vials of tranquilizer. They sail like arrows, aerodynamically shaped like a crude bird, and when they pierce the skin, there is a moment of quick, biting pain, followed by long, slow sinusoids of a deep, piercing throb, before blackness overtakes you. I have never tried to escape; I want to be sacrificed.

Today is the day of the Undoing. Most will be awake in an hour – earlier than usual. I give the butterfly a short burial. I think things that burn are things that were so holy they needed to be sacrificed. A few minutes later, I hear footsteps behind me, slow and steady. It is the elder who is getting ready to signal that it is the Undoing. I think about the body of my mother. I think about how I saw it for the last time. She was beautiful enough to be sacrificed. It is only the girls who have the Sight that receive this honor.

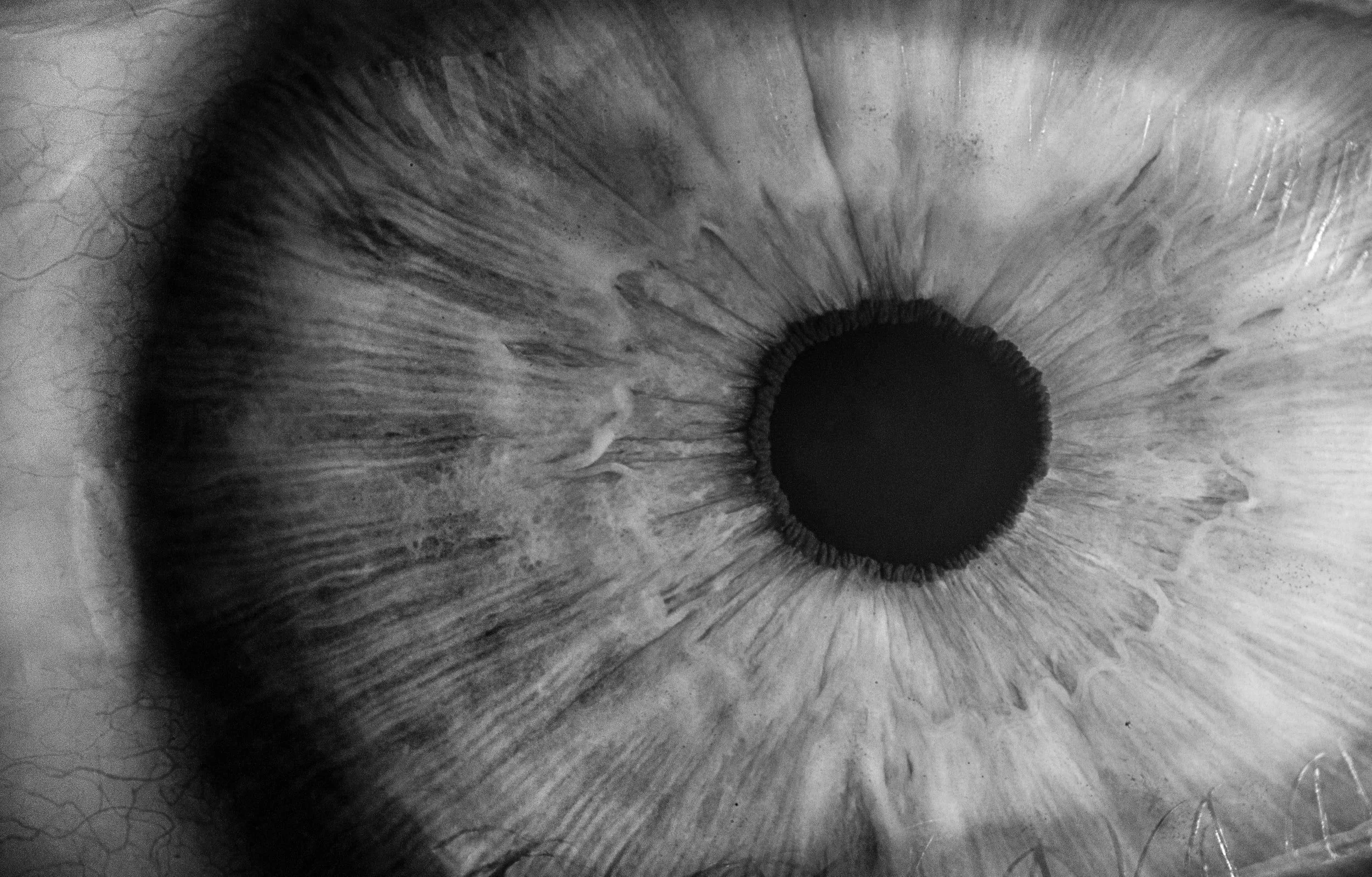

My vision is shattered, unlike the other girls at the temple; while they can see more colors than the average person, I see things that don’t exist. They call me the one who sees ghosts. I can see the death that creeps at the edges of each of the trees. I can see the end of things coming––the rot that builds at the base of the wooden furniture inside of the temple, and the bones inside the body of this butterfly. I can see what’s ugly. My head is filled with the terrible thoughts that race through the minds of others – of how defective I am, how grotesquely I walk. I cannot tell if I see it or if I am imagining it. They think I see it. Who am I to protest? So yes, beyond me, I can see colors that refuse the traditional English words from the Earthen settlers who have come to this planet. The color of amber dripping softly from the sap-filled holes of the trees in the distance, the trees which press themselves close to the ground to avoid the intensely charring rays of the sun, is a color I hold close to my heart but do not have a word for.

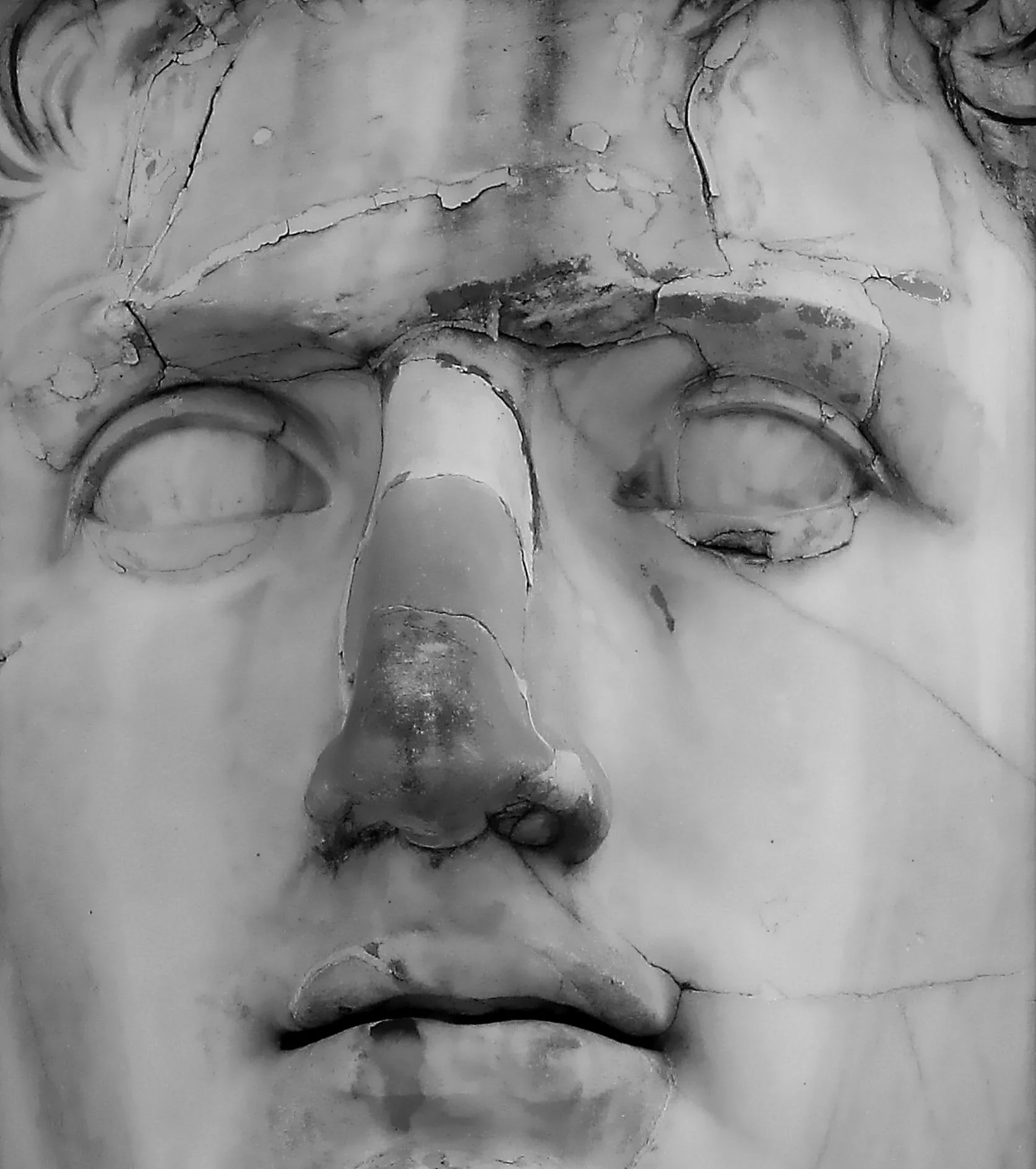

The elder pads up behind me and shuffles to the entrance of the courtyard. She looks at me like I am a statue ready for appraisal, but then there is distaste that flushes through her, like there are marred blemishes in the sculpt of my body. There are no shadows on her body, because the light comes from every direction; like a contrapposto statue, the light poses her in each instant, like a photographer’s angle. It freezes you in time. It’s not golden, and it’s not harsh, either; rather, it’s a flame of intensity that scatters down her neck and makes her a woman in control. She deems who is worthy of sacrifice.

“Why are you outside at this hour?” she says. I know she and the other four elders who have been here since I was abandoned on the steps of the temple look down upon me. In her I can see the mark of death traced all over her already – the imprint of a handmark around her neck, the fingers red and raw, so pale I know it will not come for years down the line. I look away quickly and when I look back her lip has curled with fear. She knows what I have seen, and it is sacrilege for me to say; it is a disobedience to Hou Yi. Light is time. Here we operate on lightyears. Light – therefore time – is sacred; when traveling towards light, we move in different dimensions of time. What I mean to say is that we are not allowed to disobey the linearity of time here.

I can feel her gaze penetrating my body the way that light does: like it’s encasing me in a cocoon of silence, and I am not enough. I speak humbly, still staring at the ground. “I’m outside to look at the trees this morning – to look at the work left to do in clearing the land around us.” I am here to maintain the lands here, a groundskeeper.

the color of [jade melting under the pressure of sun]

the color of [my mother’s lips parting as i am born]

the color of [my last dream disappearing from my mind]

the color of [a cracked almond rationed between girls]

the color of [a bruised-blue tongue, screaming]

the color of [death]

[ ]

i only see death

[ ]

“The forest is a place of mystery,” the elder says, shuffling down the steps. “It is a great privilege to be taking its timber, to cut it down each year to clear space for our temple, and to use the timber to light the Great Fire. But it is dangerous. When I was a child, I ran outside and explored until a wild animal chased me back in here. It was an enormous antelope, already driven mad by starvation, mutated with photosynthetic fungi that lived in pulsing craters around its neck and head. It chased me until I couldn’t breathe, until I was tripping over my own steps, until I fell over roots and scraped my knees and blood gushed from my wounds. The temple was young then. When I came back, they shot the antelope with arrows and ate its meat for the next few weeks. My mentor shouted at me for hours, telling me why I should not have gone out without help.” She shakes her head. “The forest is dangerous. You would do well to remember that it is not worth it to go beyond it.”

I know to obey her. “I won’t ever do that. I promise.” It’s a lie. When I was six I escaped to the middle of the forest and sat on the ground. I made a space for myself there. I stashed my leftover food and my first-aid, setting up a radio. When my mother found out, she tugged me aside fiercely and screamed at me in our room, telling me to destroy the evidence of leaving the temple. Camila, you will not survive without your sisters, your mothers, your aunts here. You think you can make it on your own? I never tried that again.

*

Back in the temple, I re-enter the caves where the girls live. They rustle about themselves and twitter frenetically. Jazz from a speaker hidden inside of the wall electrifies the air. Girls smear smoke and glitter across their faces, and incense is lit. Powder from the wall seeps off and infuses the air around us.

Girls stand, facing upwards, towards the hole in the center of the cave’s ceiling where light pours and puddles through, reaching the tips of their toes. I sit down quickly, using jars of rouge to smear their faces. I refuse to look at their eagerness; it hurts me a little bit. I veer far away when they walk out, prideful and preening. Jada, Lina, and I are the three girls who will not be sacrificed, and we sit by the jars of makeup that are scattered across the ground, helping them tie their white sashes and prepare. They look ethereal, and I avert my eyes so they cannot tell that I feel lesser than them. I always feel stiff here, like I’m ashamed of my wanting to be one of them. I flick my fingers across their skin, dabbing colors that we can see – glittering powder the color of shells left to dry, the color of dark brown tree bark flattening into the mixed sediment of paper raiment. Up close hair frames the faces of these girls. We all look similar, raised in the temple, our hair bleached platinum and white by the sun’s unforgiving rays, and our eyes are clear, like glass. We are spread in cots that form a circle around this radius, and we have no blankets.

As Jada is called outside by a mentor to help prepare the food, I sit down to help the girls quickly braid their hair. The ones who have kept their long hair, the older ones, who have neared 18 lightyears, twist their whitened strands into long braids. I kneel beside one girl, Caroline, and start to tug a comb through her hair. “So, what are you going to be doing for the rest of the day?” she asks.

“I’ll be making sure it all goes well,” I say.

“Yeah, I mean, you’re doing the most important job of all of us. I feel like someone has to. You’re the best, Camila,” Caroline says. She doesn’t mean it. “I’m so sorry, but can you go lighter? My head is sensitive.”

“Sorry,” I say.

“Some of these girls here are crazy. I feel like you dodged a bullet. I don’t want to be crossing the Silver River with them. I’m sorry you can’t come with us, because I’d love to have you there with us, but some of these people? Not to be sacrilegious. I do want to cross the Silver River. But it’s a long journey. You want to do it with people who are most worthy.”

The girl standing next to us, Penelope, makes eye contact with me. We both know that Caroline is like that – vaguely condescending and entirely purposeful. “That’s great, Caroline,” I say.

“I heard that Bernadette doesn’t want to. Isn’t that insane?” she says. “She’s not worth an ounce of our attention or care. Just let her rot by herself.”

I finally gather my wits and respond. “Caroline, you are going to be sacrificed, and you are going to deal with it instead of making such a grand deal out of nothing. Please stop giving us all of your unasked-for opinions.”

But I don’t say that. I don’t have the status to. I keep my head down. Out of the corner of my vision, Bernadette is still curled up on her cot, dirt still smeared across herself. “Bernadette, you need to shower in the lake,” I say, going over to her. She looks at me grimly, her gaze empty, the glassy color of her eyes not reflective and marvelous, but ashamed. I loop her arms over my shoulders silently; I have witnessed other girls just like this, nervous and faithless before the Undoing. I bring her to the outer rim of the temple at the backside of it, where there is a vat of mercury. The silver color of the heavy liquid sits as heavy as metal, with no froth or bubbles. I dip her toe in it, and she twitches and pushes herself backwards.

“Bernadette,” I say urgently. “Bernadette. Wake up. You need to do this.”

“You don’t realize what they’re doing to us,” she whispers. “I heard you don’t come back from the Silver River. I have a feeling you don’t come back.”

“Bernadette, you’re getting the same fear most girls get,” I sigh. “Come on.” I try to take off her dress and help her into the mercury tub, but she resists, clawing at my arms until she draws blood. “Bernadette! You’re hurting me.”

She scratches my arms and lunges away from me, dazed. She is swaying back and forth. “Do you know what they do to the people?”

“I have no idea what you mean,” I say. She mutters to herself. I scrub the mercury through her hair, and the silver pools around the dirt on her skin and slushes off. She rocks back and forth on her heels.

She tries to run away, but I loop my arms around her and she trips into the tub of mercury. Shivering, she washes herself. I help her scrub her hair with the thick liquid. The elders tell us it cleanses as it takes the top layer off of our skin. She bites her lip, and when she comes up, she puts her clothes back on.

do you know what they do to the people?

it doesn’t matter, bernadette, enter the mercury

Later, in the courtyard, the ground is paved with bone-colored tile, with vases of flowers stretching up from the ground. The stone tables present bowls of roasted tangerines and slabs of meat fermented with spice. Then in the great altar that stretches out like a balcony above the courtyard, the Great Fire rages. We never let it sleep, but I notice that it is starting to eat away at the timber beneath the ring of stones. Enormous gusts of thick red roar up into the air, throwing off showers of soaring sparks that fizzle and pop in the bleached sky. It is so dry I can feel the fire ravenous, ready to devour. The fire saves; it nurtures; it destroys.

Elder Penelope totters up to the top of the balcony, wearing a kimono made of brown fabric smeared with grime; around her neck sits a long necklace of teeth from an animal killed from the forest. The little white kernels have begun to gray, clinking against one another. She raises from her pocket a box from her pockets –– a tattered, yellowed box that we have preserved with chemicals, a box of matches –– now outlawed in the real world. Beneath her, in the courtyard, surrounded by the sunflowers that rise up ten feet in the air, their petals thick, full, and ignited with lavender and crimson, we fall to our knees. The fire rages upwards, its heart brighter and brighter gold. Elder Penelope cradles the matchbox and pulls out a single match. She drags it against the edge of the box, kept alive for decades, and it bursts into a miniature flame. Like an animal, it whispers, sways, and crackles, containing itself, a shapeless predator soon to engulf. It is pitiful and small, eager to join its sisters in the Great Fire that never sleeps. Like a god, it is shapeless and infinite, mutable in its immutability – immortal given enough oxygen. The world has vanquished something as powerful as fire, which may control the world. Around me the girls begin the song. Their voices rise up in harmony, quieter than the snap and sputter of the fire, which is so loud it dominates the morning. The cicadas are awed, frightful. Mt. Thymos is asleep. Mt. Thymos bows, this morning, to Hou Yi.

O, our minds being crowned with fire,

Drink up the sun’s plague, a burden to bear.

Or whether shall I say we death desire,

Our love for void and matter be an alchemy for despair?

No, to make of our solitude and burning a light

Such cherubs as our sweet selves resemble,

Creating every bad a perfect best

As lovely as our bodies, our sweat breaths, resemble.

Matter, candle, brass – we know what it is to exist.

Wax, wick, breath – transiently, we subsist.

Glow, flame, melt – our bodies return to the Earth.

Burn, smoke, ash – our souls are ready for rebirth.

Dust – as we disintegrate, our souls cross the Silver River.

Void – we become another sun in the distance.

Each inscription stands out boldly upon the stelae, the stone tablet carrying the commandments next to which the elders stoke the fire, which also bears a carved frieze of Hou Yi pinning back his muscular arms to release an arrow into the suns before he became immortal. For the girls honorable enough to be sacrificed, their souls will rise to the sky and become new suns that will bloom centuries later. In the heavens, they will be reduced to gas and nebula. They will become gods, like Hou Yi, who first hated the suns, archers that shot them down from below, before ascending above. The girls in their white sashes parade up to the top, where the fire looks down at them pitifully and lovingly, a great wave that rears its beautiful head.

“This matchstick is one of the ten left in the world,” Elder Penelope says gravely, her voice ringing out. She holds it above her head, and we look at it. We kneel. We breath. Together we are a body. Together we protect one another. “We are guardians of the sacred beauty of fire. Matter requires void. We are the wick, the last strength, the last bulwark. Every girl who enters the embrace of Hou Yi here will cross the Silver River. Each of you has been chosen for the Sight – seeing colors that no other mortal can. In crossing the celestial body of the Silver River, you will join his ranks.” She drops the match into the roaring flame, and the small fire joins its great body, just as our souls will join the cosmos. But even before it, I can see the death written on these girls. It is not noble. The charring appears the moment the decision is made – colors that mark their bodies. Gashes and blisters that bubble up, a second skin, on the women in white dresses lined up; blackened, browned, no longer recognizable.

I scream out and fall to my knees. The vision torments me, every one of the girls around me crisped to ashes. Somebody pulls me upwards. It is one of the elders, who fiercely berates me and drags me backwards, kicking. “Never before,” I am crying hysterically. “Never before.” In no past year before have I seen this. But it is also the year they declared me insane. “You will not pass!” I shout. “You will not!”

One by one, the girls take a step forwards to join the great fire. They ascend in a blinding light. They are silent. I wonder what their last sight is. I am still shouting, each of them shuffling forwards, the rashed cavities of the flames scorching them away blooming in my eyes. I thrash and curl into myself, but a hand grips my chin and forces me to look. It is Elder Pila, my mentor, who has guided me through all these years, even after my mother was sacrificed. Elder Penelope is shouting at her to take me away, that my insanity has grown too fearsome that is disturbs even the ritual that defines our temple. Pila, whose face was once soft with kindness, drags me downwards to the underground chamber beneath the temple and drags two bars across the door, locking us inside. The windows at the edges at ground-level give us a view of the inferno engulfing the bodies of the girls.

“What are we doing?” I sob, frightened. I back up against the wall. She flicks something mechanical, and a contraption lights up – a tear-drop- shaped, transparent container, which glows like a firefly upon her command. “Bernadette.” I throw my hands against the door. “She was right. I need to get her –”

“Camila, stop,” Pila says sternly. She towers over me. “You have a sight that nobody else has.”

“Don’t call me insane,” I say. “I can see it so clearly. Every death that I see, it comes true. Pila, please don’t lock me away.”

“When you were a child, I thought you were merely poorly skilled with the Sight,” she says. “Now I see that you have been cursed with something else.” She looks at me as if I am no longer the child she brought up, teaching the rules and worship of the temple, but with strange, fearful disgust. I remember, suddenly, Pila telling me about how she burned her own daughter’s finger in the fire to stimulate her into combat training. How she disdained civilians who lived like animals below the mountain, descending into debauchery and lechery, and how she stripped a man of his clothes and let him starve in the woods when she found him on our territory. I remember that this woman has many sides than the one who nurtured me. I scan my surroundings rapidly, taking stock of where I am. It is a storage inventory here. Tall shelves full of bound, rectangular leather containers, ones which I suppose must store perishables, like fragile foods; a cart full of rusted knives, which must be old ones that were discarded years ago. A fireplace that still rages dimly.

Pila seizes me by the wrist and drags me forwards. From the cart she slides out a rusted knife and holds it to my wrist, trembling with fear, her eyes blown wide like an animal’s. Sweat drips down her forehead. “I don’t know what you are. You saw their deaths. Tell me. Tell me how you are doing it.”

“What do you mean?” I whisper, shaking, leaning away from her face, which has now been thrust close to mine. “Please – Pila, I don’t know – I just have it. Is there something wrong with me?”

“Tell me how you do it,” she says, and dips the poker in the fire and draws it close to me. “I trained you to never fear pain, but I know exactly how to hurt you the most.” She draws it close to my skin, and I know she is a woman who will not hesitate to draw shapes upon me. I throw myself backwards and hit the shelves, where the rectangular objects thud to the ground and spill open. Rather than unlocking to reveal their insides, they flip open to reveal hundreds of paper pages bound together, with craggy lines of black ink crammed together on them.

The door unlocks with a series of clicks, and another elder steps in. Pila swings her head upwards, letting the poker go with an immediate clatter. “She’s unruly,” Pila says, trembling, stepping backwards. “Her Sight. It’s not – it’s not right. She’s an anomaly. We always knew there was something wrong with her; she was never as gifted as the other girls. But it’s awoken. Her insanity. We cannot let it infect – ”

“Move,” Elder Penelope says, briskly walking past Pila. She inspects the still-glowing poker and the rusted knife askew on the ground. “It is done, Pila. This year’s ceremony.”

Pila lets out a deep breath, looking up at Elder Penelope with reverence. “I am glad. What should we –”

“It is no longer your issue to concern yourself with,” Elder Penelope says coldly, and gestures for me to follow her. Shakily I stand up and walk closely after her. Up close, her skin is wrinkled but firm, wrapping perfectly around her joints, like a wrapped mask. She smells of daffodils crushed to pieces and left to ferment in an old cabinet, but tangy, metallic. It is here when I realize that the elders say they have no hierarchy between themselves, but there is. Elder Penelope leaves, and Pila scurries out to the courtyard. I let myself have one glance, biting my mouth. Corpses scatter in a circle around the bonfire, but their white dresses remain pristine and clear. It must be fireproof material. The same sight I see every year, but instead of thinking of their spirits rising, as I am told to imagine each year, my vision is sharp, granular, and tainted. Everything is thrown into intense relief, each particle and molecule scraping and bobbing and swelling. The dark shadow of death haunts each girl’s face in each blistered rash. It turns my stomach.

We arrive at the top of the balcony. Elder Penelope’s hands are full of rings. She slides one off of her finger, a thick bronze one. It has the symbol of a crescented sun on it, like a fruit someone has taken a bite out of, but the unmistakable rays are carved around it. She places it in my hand. “You’ve awoken.”

< back | table of contents | next >