Believing What You See

on Gestalt illusions, love, & pointillism

written by meilan haberl

illustrated by emily cai

A boy I love calls me from 5,270 miles away.

It’s the first time I’ve heard from him in almost four months — a short eternity — but we’ve been friends since middle school. What’s a handful of weeks, compared to a decade of knowing and growing? It’s a miracle, in many ways, to still be connected. To be able to hold a tiny box of metal and glass and plastic, and listen to him. Over the phone, his voice is sometimes tinny, sometimes robotic. I imagine it as a coiling wire, spiraling across the ocean, stretched thin during the occasional pocket of static, strong when it ripples with the familiar warmth of his laugh.

While I listen, I dig my feet into the damp soil of Prague’s Letna Park. It’s a muggy summer evening, but the trees are thick and verdant, the twilight dusting the park’s greenery in gold. Even as I try to plant myself in the ground, I feel adrift; I’ve just recovered from my first battle with COVID. After spending so long miserably ill, curled up in bed, feeling like my bones were made of frigid glass while my body burned with fever, the park’s immersive loveliness feels bizarre, an overwhelming sensory miasma of beauty.

It helps to focus on my friend’s voice,

to tune everything else out,

as he describes something he calls “analysis paralysis.”

Google has a perfectly serviceable definition of the term. I like the way he explains it, though: an omnipresent, pressing, suffocating sense that he needs to start walking, choose a life path, be moving towards something—but his feet are frozen in place.

but the world feels so huge, so crushingly consuming.

but what if,

what if he gets hurt?

what if he makes the wrong decision?

what if he isn’t good enough?

what if he isn’t worthy?

The last bit isn’t something he said—not word for word. It’s something I hear

from one of my best friends at college, one of the most accomplished and capable women I know, who runs herself ragged trying to get it all right,

from a friend older than I, who has lived all over the world, whose brilliant analytical mind is matched only by their boundless creativity, who has lost incalculable nights choking after having bitten off more than they can chew, overwhelmed by the impossibility of accomplishing what they’ve set out to do

from countless conversations in dining halls, posts on social media, late-night Snapchat messages from people I’ve known all my life.

That miraculous device, the phone I use to shrink several thousand miles to a few seconds of delayed connection with my childhood friend, warps more than just my perception of space and time.

This is not a new or original thought: innumerable thinkpieces, youtube videos, and daytime TV commentators have raged against the perils of seductive screens that suck the life force from The Youth. Sometimes they are bombastic. Sometimes, as in the case of American psychologist Jonathan Haidt, they are actually doing research, research that shows the troubling correlation between our social media screens and astronomical rates of anxiety, depression, etc.

Still, my phone is a wondrous device, allowing me to stay socially close with the people I love, no matter where in the world I am, no matter how physically distant or quarantined we may be. It is also a magnifying glass, a microscope, a not-so-funhouse mirror—and through this looking glass, there is so, so much to be seen.

Terrible things—wars, shootings, injustice, on a macroscopic level. The casual cruelty of a comments section, devastatingly private information blasted callously around the world in a matter of seconds, the kind of misinformation that costs lives.

Wonderful things—love, courage, resilient compassion. We can visually record the truth in a way that serves justice, send kind words or material assistance to struggling strangers around the world in a matter of seconds, spend time with those we love in impossible pandemic circumstances.

It’s a miracle. It’s a curse. It’s addictively stimulating. It’s overwhelming.

There is so much to see, to change, to choose. Too much.

“Analysis paralysis.”

How can we deal with it?

When I was little, a museum trip with my parents introduced me to the concept of Gestalt Psychology. I barely came up to my dad’s knees—he had to lift me up so that I could peer into the museum’s display cases, exhibitions that demonstrated the visual illusions and objects that modeled the perceptual phenomena observed in Gestalt psychology. For a practical example: consider the following image — what do you see?

An old woman? or a young one? Can you see both? Neither?

When I was little, I saw the young woman clearly and immediately, and struggled to see the elder. Now, I can hold both in my mind — though it takes a bit of effort.

This kind of illustration is characteristic of gestaltism and what Gestalt psychology can reveal about our ability to perceive.

Gestalt psychology is a theory of perception, developed by a group of early Czech and German psychologists at the start of the 20th century. These psychologists — Kurt Koffka, Wolfgang Köhler, and Max Wertheimer — were responding to another, earlier theory: Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Brandford Tichtener’s structuralism, which sought to isolate and reduce complex psychological processes into their most basic and individual components. Structuralists believed that examination of the mind was best served through this molecular approach. They trained introspection as a tool of self-scrutiny; a lens through which one could dismember internal experiences into static components that might then be appraised from a detached, objective perspective. By contrast, the Gestaltists held that true insight into the mind could not be gleaned from such atomistic, removed analysis. Instead, they advanced a noetic theory of totality:

the mind is a summation of all the dynamic processes therein,

with no one part less or more important than the others.

The elements that comprise it, that comprise us, cannot be fully understood independently, as disjointed cogs and dissected joints under a microscope.

Instead, one must consider the whole as a whole:

integrated,

complex,

complete.

In order to totally examine totality, the Gestaltists developed principles of organization and perception, which describe the fascinating patterns and trends of human perspicacity that cause us to see and interpret a thing as a whole, rather than the sum of its individual parts. These laws identify real, perceptual phenomena, but also speak to the tantalizing hope that we can assemble some sense of order out of chaos, that there is a hidden method to the madness of life. This hope underlies the connotative nomenclature of many a Gestalt principle of organization: the law of closure, common fate, the principle of good continuation.

Though lovely in name, these principles describe patterns of perception that you may not find particularly interesting or insightful, when described in layman’s terms:

closure→ we trick ourselves into seeing incomplete or separate things as a completed whole (for example, this 🫥 looks like a face in circle, right? But the circle is just a bunch of dashes)

common fate→ we group lines, objects, or shapes that operate in parallel together

good continuation→ if lines touch, we assume they are connected

However, like so much of Gestalt psychology, these principles are meaningless when individualized, disconnected from each other and actual application to life. Moreover, making meaning—as I hope you will soon agree—is merely a matter of perspective.

We will return to closure, common fate, and good continuation;

but for now, in the interest of returning to our question

“How do we deal with analysis paralysis?”

I will instead direct your attention to

three other Gestalt principles:

multistability

reification

&

emergence

and the lessons they can teach us.

On Multistability

Remember our lovely lady friend?

She is but one of many optical illusions that display the Gestalt principle of multistability, also known as multistable perception. Multistability describes an instability, but also an ambiguity of perceptual experiences — limited not just to sight, but present also in auditory or olfactory sensations as well — where multiple, alternative interpretations of a thing coexist. Whatever the multistable entity is, our perception of it may flicker back and forth between its multiple interpretations, or we may struggle to see it beyond our initial interpretation, or be unable to unsee a secondary perspective, once we’ve spotted the first.

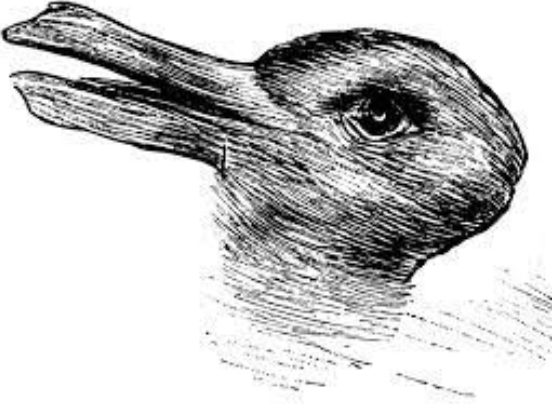

Frustratingly, Gestalt psychology does not explain how multistability works, only that it does. However, exploration of multistable perception has elucidated a number of fun and/or confusing optical illusions to befuddle the senses. As you view the selected multistable figures below, consider the following questions: what did I see first? How quickly did I assume that I knew what I was looking at? Can I see the other perspective(s)? If so, is it difficult? Can I see both interpretations at once? Do I see neither?

Face or vase?

Duck or rabbit?

How old is she?

It should be noted that these three examples are fairly black and white, both in the literal chromatic sense, and because they are designed to show precisely two different perspectives.

Life is rarely so simply delineated between black and white, between contrasted extremes. But I would argue that at second glance, these multistable bodies actually provide an apt metaphor for the complexity of life: though they seem at first to be comprised of separate, contrasting colors/objects, these illusions can only coexist in tandem—one is not possible without the other, nor would they be interesting without their counterpart. Black and white are not separate, but inexorably intertwined. Arguably, the rabbit-duck even shows a few shades of grey. With a bit of effort (and perhaps the consultation of a friend) it is possible to adopt more than one viewpoint, to step into another perspective.

Further lessons gleaned from multistable images:

— our minds can and often do jump to an immediate conclusion, quickly taking in a lot of information and rapidly fitting it into a particular narrative.

— however, as in life, multistable images are often more ambiguous than they first appear. Taking time to engage more deeply with an experience can reveal previously invisible nuance. This doesn’t mean our initial perception is wrong. It does mean that sometimes we ought to invest a little more time in unraveling something. That, perhaps, we should examine — a feeling, a reaction, an immediate thought process — from multiple angles, rather than trusting our snap judgment, rather than accepting one viewpoint as an unquestioned absolute.

— And, because there are always multiple points of view: more than one thing can be true at once.

Regardless of what color the dress actually is, it is certainly true that to some people it is black & blue, and for others, white & gold.

The beauty of a park in Prague at twilight, sunbrushed gold skies collapsing under the descending weight of a sweltering summer night, can be at once stunning and sensory overload.

A person can be both wildly successful and miserably depressed.

My phone can be a near-magical wonder, while also presenting an addictive trap.

You can be hurting (traumatized, even) and still inflict pain (trauma, even) on others (and vice versa.)

My college friend can be terrified that she won’t make the “right” decision—but maybe every door that is open to her will end up being alright, in the end.

I can long to be physically beside my friend, and overjoyed to hear his voice even from overseas, and be bitterly disappointed that we are not closer after a decade of friendship, and grateful that even after ten years, he’ll still pick up the phone—with no one emotion contradicting the others. Each piece

fits into the whole,

enhances the others,

makes our relationship what it is.

2. On Reification

There’s not actually a triangle there. Or a cylinder. Or a sphere. Or the Loch Ness Monster (especially unfortunate for the cryptid lovers amongst us.) Reification dovetails with the aforementioned idea of closure, in that it describes a phenomena in which we experience or perceive more than what is actually in front of us, assembling intangible wholes out of the disparate parts that we can see. We treat that which is not real as if it was.

Reification highlights an important paradox: we cannot always trust our minds to tell us what is really there. Our perception is limited; even if we have all the pieces of a puzzle, we might not assemble them accurately. Re: figure C — we see black cones, and only imagine the sphere. But that does not mean that what we feel in response to our imaginings should be discarded, that our reactions are irrelevant, that we should dismiss our reactions to negative space as unreal.

Expanding on what the paradox of reification can teach us:

In Figure A: there might be no triangle, but we still perceive its absence as a presence.

The absence of that internship you weren’t offered can certainly be a presence in your life—a weighted sense of shame, a crushing disappointment, empty air where you thought your next step would be. Those feelings are real. Respond to them accordingly: let yourself be consoled by comfort food, release your frustration by running, be miserable for a bit, as the case may be. But then take a moment to zoom in on Figure A.

What at first seems like a triangle is actually just

a trio of these little random Pacman guys.

You might have arranged your life around the possible presence of the internship. But in its absence, zoom out, take note: the skills you put into your application, the ambition that carried you through to applying, the interests that led you to engage in the courageous venture of putting yourself out there — all the other pieces of your life — you still have those. They did not disappear, they did not depend on the acquisition of the internship. You can rearrange these pieces to build something new, to pursue something different. The absence of the next step on your path need not interrupt the trajectory of your journey overall. Sure, you might have to take a running leap to get to the next step. Or you might innovate a new way to keep climbing. Or you might take a leaf out of Pacman’s book — heading off down a different path, outpacing the ghosts of absentia.

Figure B: in the absence of a cylinder, the two blobs becomes something more.

The aforementioned psychologist Jonathan Haidt is interested in exploring the ways in which social media interacts with mental health in youth. There is certainly data to be mined here: recent research shows correlations between increased use of instagram and body dissatisfaction, decreased self esteem, anxiety and depression. It’s an easy trap to fall into: scrolling through your phone, comparing yourself to every beach vacation, every glamorous selfie. Engagement announcements metastasize into “why am I not in love yet? Am I unlovable?” and “why wasn’t I invited? Are we even really friends?” are toxic derivatives of group party pics.

What we perceive as the absence of these things in our own lives heightens our perception of their presence in others’: posts become a guarantee that everyone else is happier, more beautiful, more beloved, more wealthy, more sane, more successful than we are, immaculate images enshrined by an Instagram filter.

But

as we know from multistability and reification:

our immediate impressions of an image are not necessarily reflective of the truth.

Or at least, not a complete and nuanced truth.

What we see may not be what is really there.

Our viewpoint is limited — restricted to the perspective of a viewer, examining an amplified, warped representation of a few disconnected facets of the viewee’s life, magnified by the funhouse lens of our phone screen. And what is it magnifying? Colored pixels under a piece of glass. No more real to you than an invisible cylinder and two squiggles of black ink.

Another paradox:

Image, its influence, and our imaginings about what image signifies, are all important to unravel, to examine and consider.

Also, image isn’t everything.

And seeing does not have to mean believing.

Figure D: Loch Ness jokes aside, human beings are certainly capable of constructing monsters to haunt our psyches. Ghouls and ghosts linger in graveyards and fireside tales, werewolves and vampires prowl the pages of folklore and YA literature alike, while ancient curses and Kaiju stalk the silver screen. In modernity, creatures that go bump in the night have gone from frightening supernatural figures to campy punchlines. Perhaps this is because we face far more terrifying natural forces, the kind that cannot be dispelled

by a silver bullet or blessed cross:

Climate change and global warming,

a world on fire.

A pandemic that killed millions,

while millions more refused

to simply put on a mask.

I can’t touch a pandemic, can’t see it. Can’t even hold the massive number of the dead in my mind’s eye. Global warming doesn’t scrape its claws against my front door, rattle my windows, or threaten to suck my blood. But I can feel the terror of it draining away my hope, my future, all the same.

Other monsters are visible, and of our own making:

Radicalization wormholes

wriggling through every corner of the internet

spreading lethal misinformation, eugenics,

fascism like an infectious plague.

An inability to see the humanity in one another,

to take the perspectives of other people

who are suffering, who are struggling,

too much under the weight of our own pain

to bear the burden of anyone else

to glance up and see them. Instead we atomize

the world down to

black vs. white

(no other colors allowed)

life down to friend vs. foe

friended vs. unfollowed

ally vs. anti

with no in-between

The world burns while we tear each other apart on Twitter.

How do we deal with any of it?

I don’t know.

3. Emergence

I’m not a monster slayer.

What I am is an exhausted college student deep in the trenches of finals, struggling with all the usual, mundane ailments: writer’s block, uncertainty about the future of the world, financial stress, anxiety about the next 24 hours, loneliness, the frivolous state of being caught between the increasingly pressing desire to sleep and the equal and opposite compulsion to keep working past the pretense of productivity.

I am not quite at the point of analysis paralysis, but we’re getting there.

In writing this piece, I keep having to avoid overusing the word “overwhelmed.” There’s really not a better term for this state of being. Sensory overload. Too much stimulation. There is so much happening in the mind, all the time, whether waking or sleeping or somewhere in between —

— and that is precisely what our final principle, emergence, addresses.

Emergence describes a confluence of psychological processes from which consciousness arises: the idea that through the synthesis of many systems, a coherent entity irreducible to, and not defined by, its individual parts emerges. Although lower order constituents may be examined on their own, this principle holds that base elements cannot predict the shape of the whole until it all comes together.

Accordingly, here we will synthesize the aforementioned Gestalt principles of organization into something altogether new.

Consider the following creation, “Child at Heart I,” by artist Betty Acquah — and do not just consider, but pause. Ponder. Examine the composition. Contemplate different interpretations. Zoom in. Bring together that which we have discussed so far with what you are seeing now.

Here are our principles of multistability, reification, and even closure, common fate, and good continuation — emerging into something new.

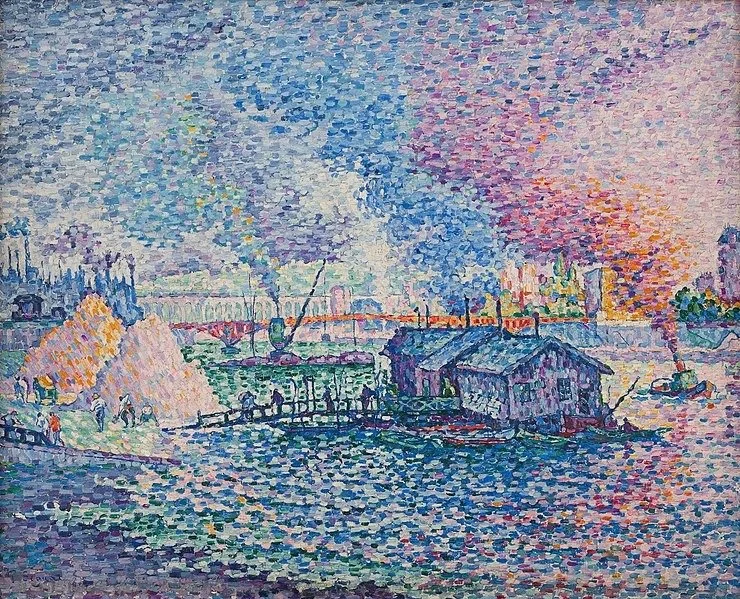

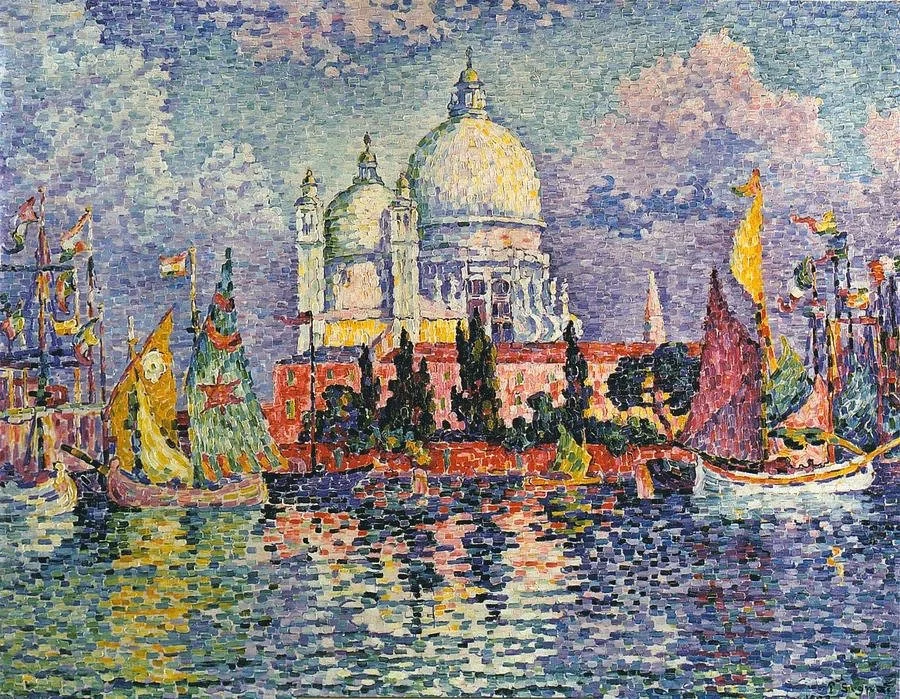

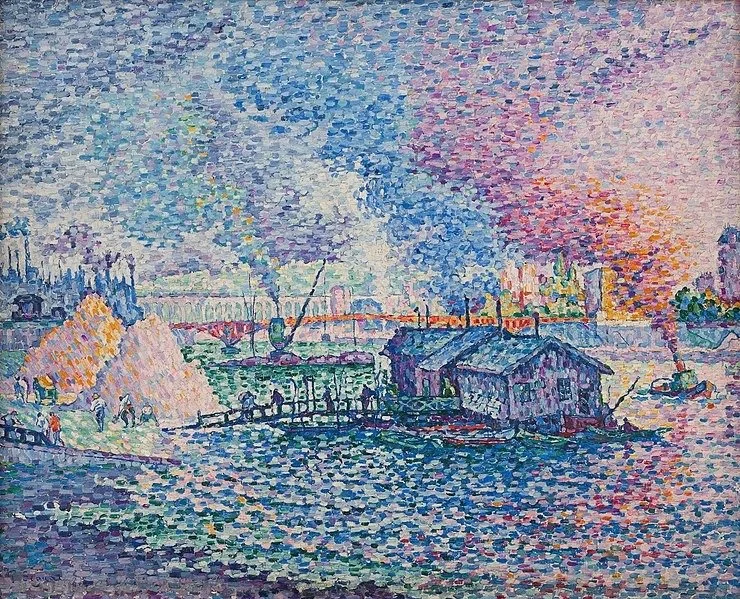

Here’s more. Paul Signac’s “The Pink Cloud, Antibes,” “The Salute,” and “Mirabeau Bridge”:

Look at the detail. This painting style is called pointillism; using only individual dots or daubs, artists orchestrate patterns into a coherent painting. Follow the individual strokes, the choice of colors, the bubbling shape of the clouds, the way the light reflects off a sonorous sea composed entirely of colorful dashes.

Can you name every color? Detect every trick of depth and deft manipulation of contrast? See both the individual brushstrokes and the entirety of the church, harbor, sea and sky?

Trying to do so is (there’s that word again) overwhelming.

Holding together one’s sense of sanity, when there are so many things to keep track of, so many things to do or to see, to feel and interpret and consider and perceive — it is too much. Paralyzing.

I don’t have a magic cure for this.

And the point of this piece is not to make you feel less overwhelmed — because you have good fucking reason to be overwhelmed!

But “overwhelmed” does not have to be a death sentence, a one way ticket to the purgatory fields of Analysis Paralysis.

So many of us are struggling with a sense of being overwhelmed by the myriad stressors that life has in endless supply, a seemingly infinite flood of losses, cruelties, pains great and small, with the suffering of the past as a looming threat at your back, and the insecurity of the future a gaping pit before you. Every move feels like it could send you tumbling into the abyss. And yet — we don’t have to see it this way.

Have another look at our pointillism pictures:

From a more remote perspective, these images hopefully don’t seem quite so frenetic or overstimulating (if so, emergence and reification are at play). Before, I asked you to try to keep track of every point, every color and line and form. Now, I pose a different question: is there anything misplaced in these paintings? Any stroke that clashes with the others, that ruins the painting, renders it ugly and incoherent?

When we are deep in the frigid trenches of analysis paralysis, it can feel as though any action could lead to a fatal error. Yet no one mistake, one misstep, should ruin everything, destroy the manifold composition that is your life.

I say this not to minimize the very real horrors and harms of modern existence, or to pretend them away — they are real, and awful. But neither should we allow our fear of failure to so ensnare and incapacitate us that we hide from the beauty of living. Beauty, too, can be overwhelming, as can joy and love. Contrary to the Gestalt approach of totality, it can be nearly impossible to absorb anything in its entirety without being wholly overwhelmed—not that that is the practical lesson you should internalize from their theories.

What, then, should your takeaways be?

To begin answering this question, we must first return to the principles of organization that we left behind so long ago. As previously mentioned, their positive names belie less than interesting effects — but what if we adjusted our perspective? Approach the implications of these phenomena in a way that strives to integrate them into our understandings of perception in more meaningful ways?

closure→ we trick ourselves into seeing incomplete or separate things as a completed whole We have the ability to imagine what does not yet exist, to take incomplete pieces and envision something new.

common fate→ we group lines, objects, or shapes that operate in parallel together When we see birds flying together in a flock, they seem as one entity, one body, and one movement.

good continuation→ if lines touch, we assume they are connected Connection is always a possibility. We are interconnected to so many things, seen and unseen, that influence us in ways we can never know, can sometimes barely perceive.

— When we adjust our perspective, we can adjust meaning, enhancing value in the way we see the world.

On the last point of good continuation, the idea that we are connected, is also a lesson that can be gleaned from emergence. “Overwhelmed” can be an isolated feeling—analysis paralysis even more so. But just as we are our own complex, multifaceted consciousness, we are also ourselves part of a bigger picture, a greater whole. We are inexorable from one another, no matter how isolated, how distant and alone we may feel. We are always, always connected to others,

from the people we see on a daily basis

to those who grow the food we eat

to the ones who share our values

(even though we may never meet)

to the people we have not yet met,

who we will change

even as we are changed by them

And those we will never know we have touched

Who may be fighting our same battles

Struggling against the same monsters.

You do not have to face the Analysis Paralysis on your own.

You do not have to be swallowed by a sea of individual variables,

drowning under the weight of everything you are trying to hold

trying to “fix” your emotions so that you no longer feel overwhelmed.

Gestalt Psychology is not concerned with how a thing happens, simply that it does. There is no spiraling into the past, only examination of what is happening in the present, and consideration of how we can approach it holistically.

Last lessons:

Whatever you are facing might at first feel strange or overwhelming, but

there is always another perspective to take, a different approach that might offer more insight. Orient yourself in the gray–nothing is ever just one thing

Sometimes, what we perceive as being real

is not actually there

even if the way we feel and react is.

When all the doubts, the uncertainties, the

what if

what if

what if

threatens to drown you—

— dig your feet into the ground

focus on what you can hear —

the sound of a beloved voice,

wind in the trees,

your own breath

or what you can feel

be it pain

warmth

love

grief

fragility

sunlight on your skin.

Dig your feet into the ground —

— start walking.

And remember that you are connected —

to me,

to us, to everyone, everything around you,

even though I cannot hold your hand,

even though you might be 5,270 miles away.

We are still in touch

Even though you might not always feel it

Sense it

Perceive it

Believe it.

Artist’s Statement

Ironically (but entirely predictably) this piece was exhausting and overwhelming to write. I owe an enormous amount and am incredibly grateful to Sarah and Roxana for their saintly patience in putting up with my inability to meet a deadline, while I followed this piece down the rabbit hole to completion. A second major shoutout to Roxana for providing the brilliant spark for and initial phrasings of “absence is also a presence, and presence can reveal an absence” that gave form and direction especially in the Reification Item B section. Thank you also for introducing the lovely word “noetic” to my lexicon.

I don’t know that there’s much more to say beyond what I tried to convey, however meanderingly, already. I hope the piece was helpful, or at the very least: interesting. I hope that you are taking care of yourself, and taking care of each other. I hope that when you find yourself stuck in the quagmire of analysis paralysis, you reach out to someone you can trust, if not to help you get unstuck, then at least to remind you that you’re not really as isolated as you may feel. It’s a difficult time to be a person. There are no simple solutions or easy answers. As we grit our teeth and deal with that reality, I hope we turn to each other to develop new and innovative ways to dig ourselves out of these messes — that we turn to each other with compassion and commiseration and the skills to put our struggles into perspective. Keep digging, keep writing, keep climbing, keep building, keep moving forward.